DESIGNERS ARE, ABOVE ALL, PROBLEM SOLVERS.

AN INTERVIEW WITH ROLAND HEILER.

Interview: 2030 / Paul Wagner

Roland Heiler, Managing Director of Studio F. A. Porsche, is Porsche Design through and through. Clothes, watch, glasses – all created by the legendary design workshop in Zell am See, Austria. As the sun is blazing down from a clear blue sky, he enquires if I travelled from Munich in a convertible. Driving through the mountains in an open 911 would, admittedly, be a dream of an idea. But no, I drove here in a somewhat uninspiring Fiesta from Flinkster. And, being in awe of Porsche, I chose to leave it in the car park next door …

Roland Heiler / Photo: Daniel Breidt

Roland Heiler, do artists and designers tap into the same sources of creativity?

That’s a question worth thinking about in more detail. I think it very much depends on the level at which you make the comparison. If you assume that creative thinking is required for both art and design, then I would say, yes, there is a common denominator. Perhaps also the tools that help a designer or artist present their ideas. But given the nature of the task, the areas drift apart quite quickly after that. A designer is basically an aesthetically minded problem solver. Design, at least as we understand it here at Porsche Design, is never just visuals, just emotion, just appearance or just a shell, but always encompasses the entire creation of a product, including its functional and technical aspects. Art, on the other hand, is detached from its purpose. And here, of course, design is very different from art. While the designer is seen as a problem-solver, the artist often highlights problems, deliberately provoking in order to point to certain issues, someone who makes his position clear. The bottom line is that art has a higher political component than design.

Don't aesthetics also have a place in art?

Of course. There are many examples of this. But the focus is often also on socially relevant topics. At least if you look at Documenta. The political, the social, these are areas that design touches only minimally, if at all.

Do drawing skills still play a role in design today?

Yes. I love using the medium of drawing in such a way that, on the one hand, it shows a representational object, but then, through a brush stroke, a completely different quality comes into the representation than if one were to simply try to depict a photorealistic image. When I draw or paint, I can achieve something that isn’t possible with a photo. And what I find fantastic, especially with the old masters, is the way they use light. You can create incredible lighting moods that exaggerate and dramatise reality.

Light, of course, also plays a significant role in the photographic representation of design objects.

Light is important in every case. Form only becomes visible in good light.

Porsche Design embodies a design philosophy in which the form of a product is derived almost inherently from its function. That’s how the founder Professor Ferdinand Alexander Porsche put it. What is the design heritage of Porsche Design?

If there is such a thing as a German understanding of design, then Porsche Design is certainly one of the representatives of this ethos. Historically, Bauhaus marked the beginning of German design. Later, the Ulm School of Design with designers such as Max Bill and Otl Aicher was influential. In the following years, there were a number of important designers who gave substance to this concept. Dieter Rams played an important role here. As a result of his achievements for Braun, he ultimately became the role model for Apple designer Jonathan Ive. Steve Jobs consciously referred to this German understanding of design, characterised by Rams, with its timelessness, simplicity and unpretentiousness. Richard Sapper was of course also outstanding. These were people who created things that were epoch making. They are role models for us, designers to whom we at Porsche Design and Studio F. A. Porsche feel a spiritual connection because we understand why they did things the way they did. Our design approach is based on the same principles. In contrast to design studios that focus exclusively on the aesthetic worlds of their customers, clients come to us precisely because of our clear design position. We stand for the opposite of decorative design, we stand for a timeless design language. This also means that we don’t commercially exploit fashion trends but remain true to our ethos. Sometimes we even manage to set trends ourselves. There are a few examples of this from the past ...

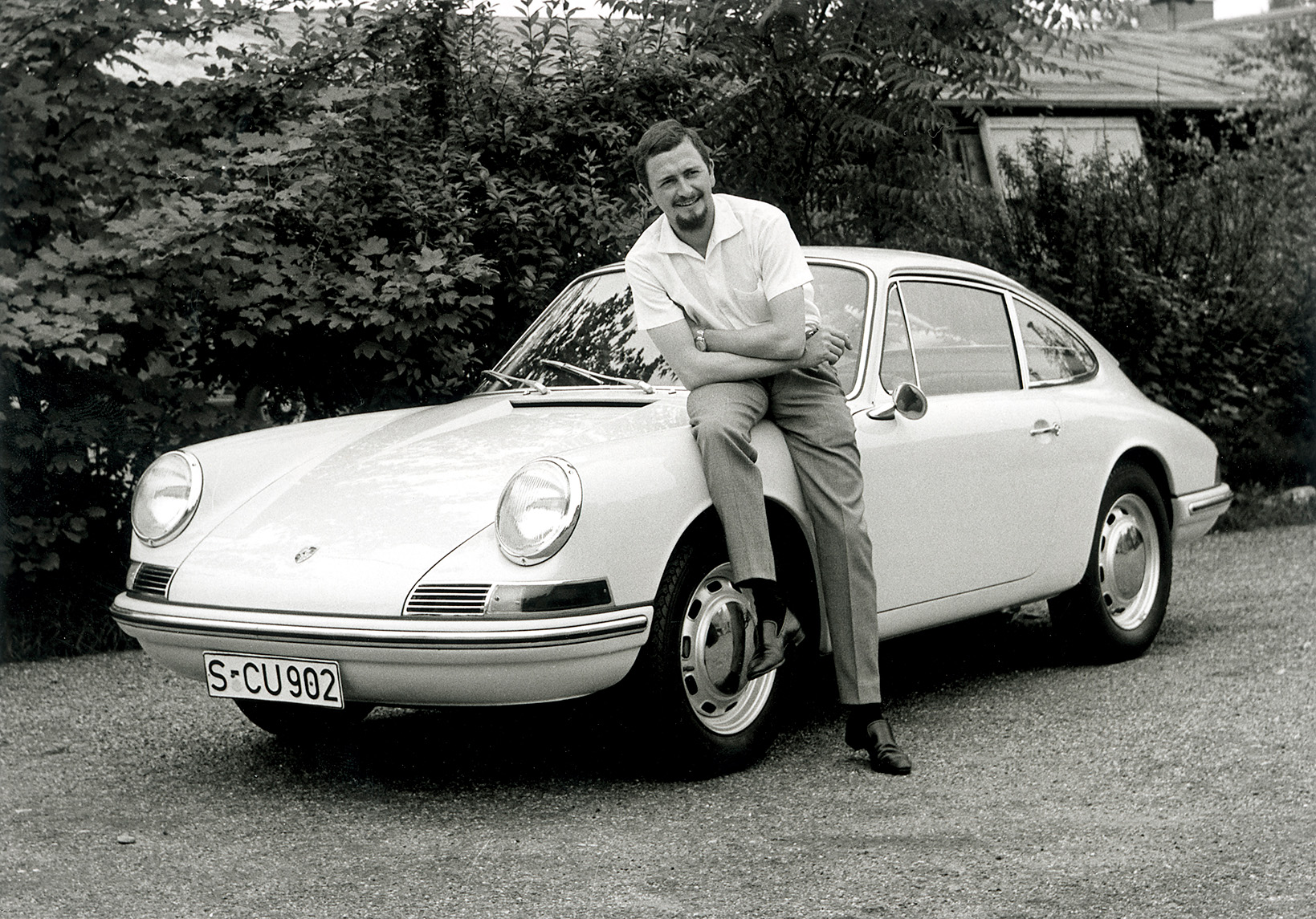

Photo: Porsche AG

Such as the legendary Porsche Design Chronograph I watch, the first sunglasses with an interchangeable lens mechanism, the P'8478 or the spectacular P'8479 worn by Yoko Ono and, most recently, the BOOK ONE.

And don’t forget the design icon par excellence and pioneer of all Porsche Design products: the Porsche 911, a product that defied all contemporary trends. Other manufacturers, including the other Swabian carmaker, were influenced by American fins and rocket tails in the 1950s and 1960s. In this context, the 911 seems like an anti-statement. However, this attitude must also be understood in the overall context of the development of the Porsche brand. It’s always been largely detached from trends and fashions. The special feature of the 911 was the technical package with the engine positioned behind the rear axle and the seating arrangement with the two jump seats behind the driver and front passenger seats. This significantly influenced the proportions and led to the 911 developing its own aesthetic. If you then take a look at how the panel seams were solved, it becomes clear that this car is an absolutely logical aesthetic statement.

F. A. Porsche said about the car that he actually wanted to design a completely neutral car. That surprises us today given the shape. But he also said that he wanted to create a car that’s in motion even when it’s stationary. I think he succeeded one hundred per cent in achieving neutrality in the sense of timelessness. No product that I know of has succeeded in proving this as convincingly as the 911, because the structure of today's 911 is still based on the original model from 1963. Within Porsche, the 911 was an evolutionary development. From the Berlin-Rome Type 64 to the 356 and F. A. Porsche's design. In the overall automotive context, it was always something completely unique.

F. A. Porsche Studio founder / Photo: Porsche AG

Did you get to meet F. A. Porsche?

Yes, when I started in Zell am See, Prof. F. A. Porsche still came by the studio from time to time. However, we didn’t work together.

How did F. A. Porsche make the jump from automotive design to product design?

I need to expand a little on that. F. A. Porsche grew up here in Zell am See among car engineers. As a result, his design awareness was influenced early on by function-oriented “problem solvers”, and one can imagine that the conversations at Porsche were also dominated by such topics. Then there was the influence of the Bauhaus tradition, namely at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm. Both were key factors that determined his particular approach as a designer. This attitude, which takes precedence over everything else, is exactly what I see as the connecting element between his time as an automobile designer and as a product designer. F. A. Porsche designed the car in such a way that it is a tailor-made suit of technical components and at the same time fulfils the requirements for driving dynamics. For the first product in his new, small design company, the Chronograph I, he was primarily concerned with creating a precision instrument, a timepiece. That's why he based the design of this watch on car display instruments rather than on the fashion or jewellery scene. Because the display quality of the instruments was important for a racing driver, he thought about how this principle could be transferred to a watch. He drew inspiration for the solution from the racing car dashboards, where everything is black and only the indices are white with very simple graphics. It was clear, easy to recognise and easy to read.

Immediately obvious for anyone who has internalised the philosophy with which F. A. Porsche approached design ...

Exactly. That was his motivation. The result was a huge surprise. When this black watch came onto the market – I remember it well, I was still at school at the time – it hit the market like a bomb. The whole world said “wow!” It just looked cool. There was also a supporting contemporary trend: in 1972, when the watch was launched, chrome was replaced by matt black on the Porsche 911. That was emerging as a new trend in finishing. In this respect, the Chronograph I, with its combination of functional requirements and the coolness of matt black, hit the sweet spot. The architecture of the case is so simple that it still holds its own alongside modern watches today. It still looks cool today. Omission is one of the recipes for success in design if you want to create something that will remain relevant for a long time.

Photos: Porsche AG

At which moment did you realise it’s going in the direction of design, towards cars?

I realised quite early on that I wanted to work with cars and actually become an engineer. And of course preferably at Porsche. Korntal, where I come from, is only a stone's throw away from Zuffenhausen. New Porsches were being driven around all the time, with every single car tested on the road before delivery. So at Porsche I wanted to design the shape. At that time, I thought somewhat naively that this was the job of the bodywork engineers. Then my father gave me a book as a present, “Wheels” by Arthur Hailey. A novel set in the American automotive industry in Detroit. In this novel, one of the protagonists was head of design at one of these large automotive companies. I found that fascinating, and that's when I realised, that was what I want to do! Exactly what this guy does. I want to design the shapes. Until then, I hadn't realised that there was a separate profession for this.

What happened next?

When I was already training as a technical draughtsman at Porsche, by chance I got talking to Anatole Lapine, who was head of design at the time. He had approached me because I was walking through the Porsche aisles in motorcycle gear, which he thought was funny. I told him the time had come for an old car because winter was just around the corner. And he said: “Come with me, I'll show you an old car.” We walked into his office. It was in the inner sanctum: the design area. And there was this beautiful MG TC from the 40s in his office! No bodywork at all, just the engine, wheels, gearbox and the chassis, which was partly made of wood. He wanted me to get stuck in straight away, he wanted me to make a template so that he could transfer the car to the drawing board. But when I asked what was behind the other doors, he said: “Next time!” From that moment on, he encouraged me and also challenged me quite a bit. I told him I wanted to become a designer. Then he introduced me to his studio manager, Richard Soderberg, and told him: “Okay, Richard, this young man will come round from time to time during his lunch break and show you what he’s designed at home, and you’ll show him how to do it properly.” I then managed to get my teacher to let me spend the entire last month of my apprenticeship in the design studio. That was fantastic, of course, and in those four weeks I put together my portfolio for the Royal College of Art in London under Richard Soderberg’s guidance. Lapine had said to me earlier: “You need a proper design education.” A little later, to my astonishment, he came to the design office in person, which was a rare occurrence. Everyone turned their heads in surprise - and saw him go to the apprentice's table, of all places. He sat down on my desk and just nodded at me for a while without saying a word. Then he said: “Okay, Roland, you can go to the Royal College of Art...” That was incredible, and I have to admit, I felt good that day...

It was evident that the young Heiler can deliver and is ambitious ...

Yes, that was an important step. I had realised what profession I wanted to learn and then looked for ways to get there. But without the luck of meeting the right people and being supported by them, it wouldn't have worked. During my studies, there was a small, momentous interlude: In 1981, the magazine “Auto, Motor und Sport” organised a design competition with the name “Successor wanted!” There was a call to design successors for iconic cars such as the Golf, the 2CV, the BMW 3 Series, the Mercedes SL and the Porsche 911. I took weeks off from my studies to take part in the competition and then I was in despair because I wanted to design a successor to the 2CV and couldn't come up with anything (laughs). Then I just managed to get my act together and, thank God, switched to the 911 at the last minute. And even won the competition! As a student, this not only spurred me on in my choice of career, it also gave me a vehicle to drive: The first prize was a 2CV.

Roland Heiler, thank you very much for this fascinating interview.