MANY HANDS MAKE LIGHT WORK.

AN INTERVIEW WITH AXEL SCHMID FROM INGO MAURER.

Interview: 2030 / Paul Wagner

Photos: Leopold Fiala

A somewhat gloomy morning in Munich. On days like this, Schwabing can be really dreary. One longs for … light. Very fitting given that we’re visiting Ingo Maurer. Axel Schmid, Head of Product & Project Design, guides us through the large showroom bathed in light from luminaires and light fittings. Ingo Maurer's lighting creations embody beauty, surprise, impressiveness and poetry. And also technical innovation. That Axel Schmid, who studied product design under Richard Sapper at the Academy of Fine Arts in Stuttgart, would discover light as the best material for himself immediately after graduating certainly wasn’t a foregone conclusion. He saw his early days with Ingo Maurer as nothing more than a brief interlude. But there were good reasons to stay.

Axel Schmid / Photo: Leopold Fiala

Axel, how does it feel when a light object that you conceived and introduced suddenly appears in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMa) in New York? Your Jetzt table lamp has been there since 2009.

I was amazed and surprised. When you work in Munich, everything has such a regional, local character. Yes, we ship our lights everywhere. But the fact that you are observed and perceived from so far away, so to speak, is a good thing. A letter arrived one day from New York with the news that they absolutely had to have a Jetzt. And they needed it immediately! But series production had only just started. As luck would have it my wife Monika had an appointment in New York that very week so I quickly assembled another one and gave it to her.

Perfect timing.

You could say that. The reason I developed the Jetzt was actually pure frustration. When you design lights at Ingo Maurer, you also produce them entirely yourself. And that’s always more time-consuming than one hopes. Especially when it comes to the amount of work that needs to be invested in assembly and packaging. Twenty minutes more for gluing here, another 15 minutes for paper cutting there, it all adds up. I was therefore really desperate and thought, it must be easier, I'll make a lamp that consists of a single part that is both the frame and the heat sink with a high-voltage LED glued onto it so that it only has one plug, no power supply unit, and then you can make it in two minutes. Done. That’s how the Jetzt was created, probably one of the first high-voltage LED lights ever.

How is the Ingo Maurer brand perceived right now?

Once Ingo was no longer with us, since 2019 in other words, we’ve realised that the future is a very important aspect for our work. The new. The unknown. The risk. It became clear to us that the older the brand becomes, the greater our past and the greater the danger that people will only see what was in the past. A few years ago, the Uchiwa fan lamps that we made in the 70s suddenly appeared and became insanely successful on Instagram. Chandeliers that cost 700 marks back then were suddenly being sold for 20,000 euros. That's when we realised that on no account should we make the mistake of concentrating solely on re-releasing these things from the 70s now. Otherwise we'd get stuck.

From an economic perspective, that would actually be a no-brainer. You could say, “We’ll commit fully to our classics. Because the market wants it.” Would be completely understandable?

One could, yes. What's more, there’s always a risk associated with trying something new. The company has clearly done very good work for a lot of people in the past. We could just rest on our laurels now. But the general conditions are also changing. A design from the 1960s plays a different role today than it did back then. Why should people stick with old technology, for example, when there are technical innovations? Isn't it important to react to the further development of spatial concepts through architecture? Shouldn’t we to consider the new demands for sustainability and reparability of our products? Not to mention the safety standards, which are rightly becoming ever stricter. Ingo Maurer is in the best position to drive innovation forward. Just as we have always done. If we were to rest on our past successes and no longer dare to try something new and bold, there would be a danger that we would no longer be working on the core of light. Then you buy components in, then you become like everyone else. Until, in the end, you only work on the lampshade. Yes, we cherish our heritage. But we devote all our energy to the future, innovation and the surprisingly new. That is simply our DNA.

Photos: Leopold Fiala

The process of finding ideas for new luminaires and lighting objects – how does that work in the Ingo Maurer studio?

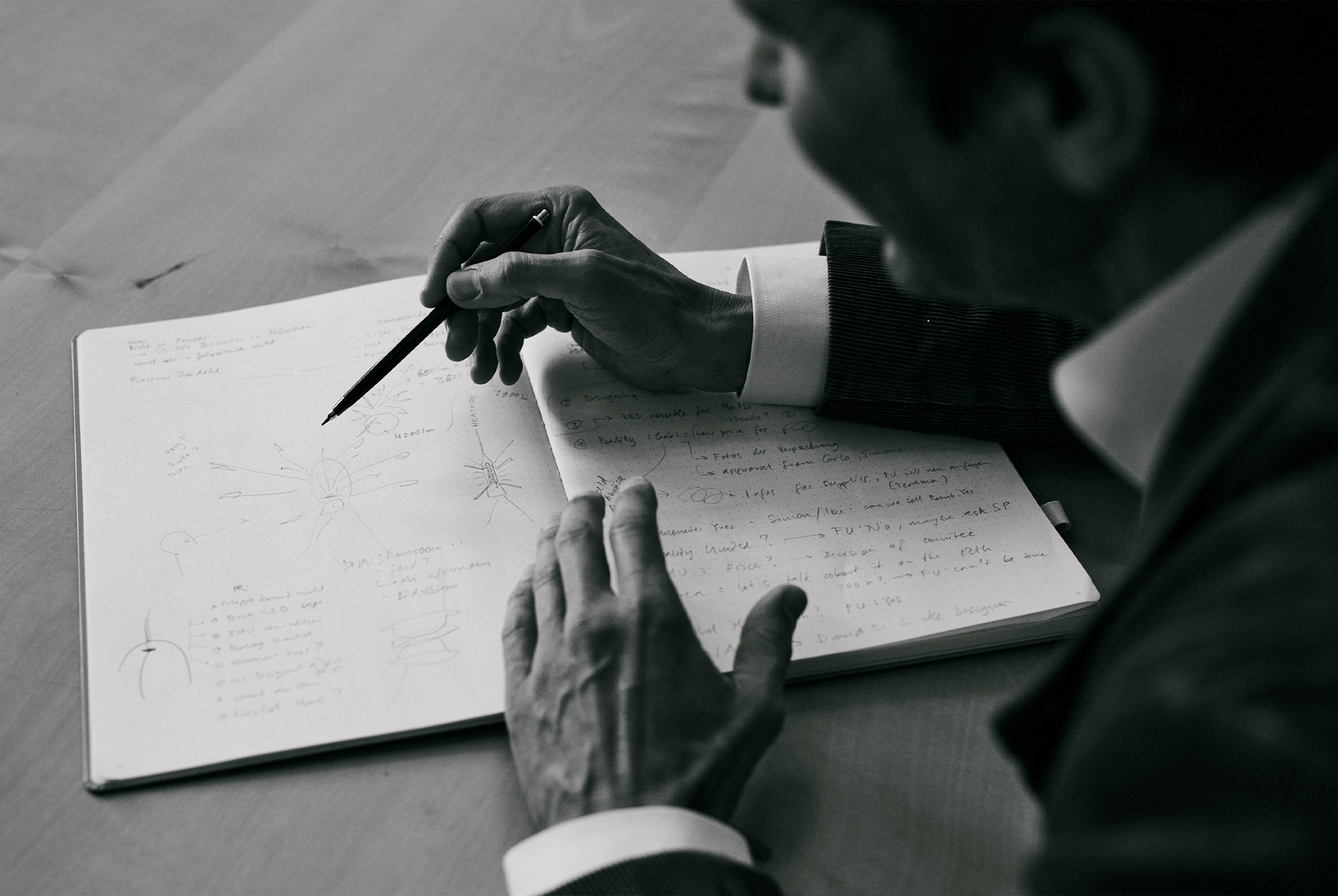

Definitely in a very unstructured way. Because light is intangible and always escapes you again and again, the process can’t be planned in a linear way. With us, it tends to be pragmatic and with no fear of seemingly chaotic twists and turns. To explain that, I always draw a sketch that clearly demonstrates what works for me, but most of all for the Ingo Maurer company. Axel Schmid sketches with a sharp pencil in his Leuchtturm sketchbook while continuing to speak. It’s rare that you have a clear and strong vision of a luminaire or a light object right from the start and that you just have to work on it in a straight line to arrive, as if by magic, at the finished result. On the contrary. At Ingo Maurer, we usually start with very small, inconspicuous ideas. They're not at all great, but they take you somewhere exciting. Especially if you end up at a dead end and the light simply doesn't do what you actually wanted. Then you need the next idea to get out of there. No matter how you then proceed, you can never be sure that the path you have chosen will actually lead to a better result. This is where the nervousness is at its greatest. In the end, only one thing counts: you have to listen to the light and be flexible. When something works, it's a huge relief. And when a luminaire is actually at a trade fair or at a customer's premises, it's very satisfying. The challenge for us is not to have a flash of inspiration in some great artistic moment, but to embark on a journey from a small idea to the finished light. The creative process, which always allows for the surprising and completely unplanned, is a big thing at Ingo Maurer.

As with all designers, your everyday life as a lighting designer is determined by timing, budgets, delivery targets, project coordination. As an artist, do see yourself constrained by economic constraints?

No, absolutely not. We aren’t held back by these issues; they are simply part of a designer’s job. It's true that in certain moments we have a similar approach, but our profession is defined very differently from that of the artist. Having to deal with hard facts is simply part of the job description of a designer . If one thought that good inspiration is all that’s needed to be a good designer, one would be misjudging many of the things that make us what we are here at Ingo Maurer: the ability to work in a team, the talent to exchange ideas with experts of all kinds to be able to meet deadlines and budgets and, of course, to inspire customers. And that includes being aware that the creative process we’ve been talking about has to be paid for. Long before the result gets to market.

A talent for educating is surely also helpful when it comes to persuasion.

For sure. But drawing also helps. I gave a course at the Hochschule für Gestaltung (HFG) in Karlsruhe called "Drawing as a tool". I believe that as a designer you have to be able to draw for two reasons. Firstly, so that you can work things out for yourself and clarify them. But then also to be able to explain things to others. The customer, the supplier, the team. What can’t be put into words alone should be put into words and images. With a good drawing you can convince your opposite number.

I can’t help but think of Ingo's napkin sketches ...

(Laughs) Yes, exactly.

What’s your opinion of digital tools?

Others have mastered this visual explanation by other means. In my opinion, the tool for this can also be a computer. I'm not dogmatic about it. Drawing is just incredibly fast, simple and universal. You don't even have to be able to draw brilliantly, even someone who draws really badly can express themselves and win another person over in this way. Drawing is also a means of creating trust in a conversation, especially with customers. Of course, light can’t be represented exhaustively in drawings, but geometries, processes, variants, directions can. That’s incredibly valuable when it comes to getting aligned. We begin, by the way, by building prototypes or models in our workshop very early on. The customer can then see these in the room and understand the lighting effect we have planned. This can also involve shining a torch into openings or working with LEDs. We’ve noticed that when it comes to light, people react much more positively to real models than to digital experiences. We’ve also had presentations with VR glasses. But that’s just not real. Of course, you could say that's the attitude of these Ingo Maurer people. But the experience speaks for itself.

Photo: Leopold Fiala

Photo: Leopold Fiala

What else makes Ingo Maurer special?

I think the interesting thing about Ingo Maurer is that we are a company that has everything in-house, from the creative process to the execution and production. That’s a fundamental part of who we are. Simply because Ingo was someone who wanted to produce his ideas himself and bring them to market, and he did.

Light very much determines the way we perceive the world. Is that a motivation for you to work with light?

Yes, light is one of the best materials. Knowing that reconciles me to the fact that I'm tearing my hair out with it.

How did you come to work with light in the first place?

I studied product design with Richard Sapper in Stuttgart, and apart from a few smaller projects, light didn't play a major role. Working at Ingo Maurer in 1998 wasn’t what I had planned. I actually wanted to go to Konstantin Grcic, but he didn't have a job to offer at the time. Ingo had stood in for Richard Sapper for a semester, so I knew him and ended up more or less slipping in with him. At first, I thought, ok, I’ll do this for six months, because it's "only" about light here. At the time, I saw the lamp merely as an object within other domestic objects, just one of many themes of creative work. During my early days at Ingo Maurer, I realised that the variety I had been looking for in the design topics was suddenly there in my everyday life. At the machine in the workshop, at the meeting table with customers, in a showroom with an audience. That's when I realised that this was an opportunity to work very universally. It had nothing to do with light, but rather with the fact that the company really tried to do everything itself on a small scale. And because this company was so "strange", it also had the freedom to do everything exactly the way it wanted.

This special, small company with its we-do-everything-ourselves culture then won you over to such an extent that the 6 months ...

... turned into over 25 years. Yes, exactly! For whatever reason, I’m wired to want to bring the things I deal with to a conclusion. This company gives me the opportunity to do that. Especially the freedom to convince customers of something that didn't exist before. Ingo Maurer's motivation from the very beginning was to push boundaries and go where no one had been before. In terms of thought and action.

How does it feel for a lighting designer to have a hit?

Very good, of course. Our installation at Porta Nuova as part of the Salone di Mobile in Milan last year is a recent example. We were very open on a traffic island and the audience consisted not only of visitors to the Salone but also of normal passers-by. Then you see a Milanese man walking past with his dog and he stops in complete surprise and amazement. To see this astonishment on his face was uniquely beautiful.

Can you describe the "Light– Floating Reflection" installation in a little more detail?

The starting point was a former city gate with two low buildings on the right and left. With a magnificent archway, we knew immediately that something quite extraordinary had to go in there. An installation, not just an Ingo Maurer logo banner. The assembly specifications for the installation were very strict. Because, of course, it’s a listed monument. So we thought about how we could get something up in the air with as little load as possible that would have something to do with light and with Ingo Maurer and would also work in daylight. After all, you can't overcome the sun. So we had to come up with something that had to do with the theme of light and picked up on the light from the sun. On the ground beneath the arch we placed a 30-metre-long walkway painted in fluorescent colours and above it filigree fishing nets with over 15,000 reflective foil flags that moved in the wind. Depending on the angle, they reflected the colours and also made a wonderful rustling sound. People were thrilled. A man photographed his poodle on each of the different coloured areas, someone rollerbladed between the colours and the nets, doing pirouettes. It was just great to see. The installation had a twofold effect on people. The immediate effect was that they were surprised and brought to a halt. But it didn't stop there. They began to engage with the installation by changing their perspective and moving within it. You could see that they were thinking about it and playing with it. That’s what occurs when you let things with no overriding purpose happen in a public space. Then you make people ask themselves why it is actually there now? Thousands of people were there.

Is it possible to incorporate this ephemeral, sacred – or however one describes it – in such an installation into series products?

It’s not easy. With design products, the fact that they have to fulfil a function provide a service and meet an expectation plays a major role. You have to be able to sit on a chair. A cupboard must be capable of being filled. A luminaire must give me light. With all the technical parameters that I can name in a catalogue concerning the light of a lamp, one thing is clear: people only feel it when they see it, explore it, when they hold their hand in the light. And then the question arises: can we live well together?

With your wonderful lights, for sure. Thank you for the interview.

Translation: Steve Hyde